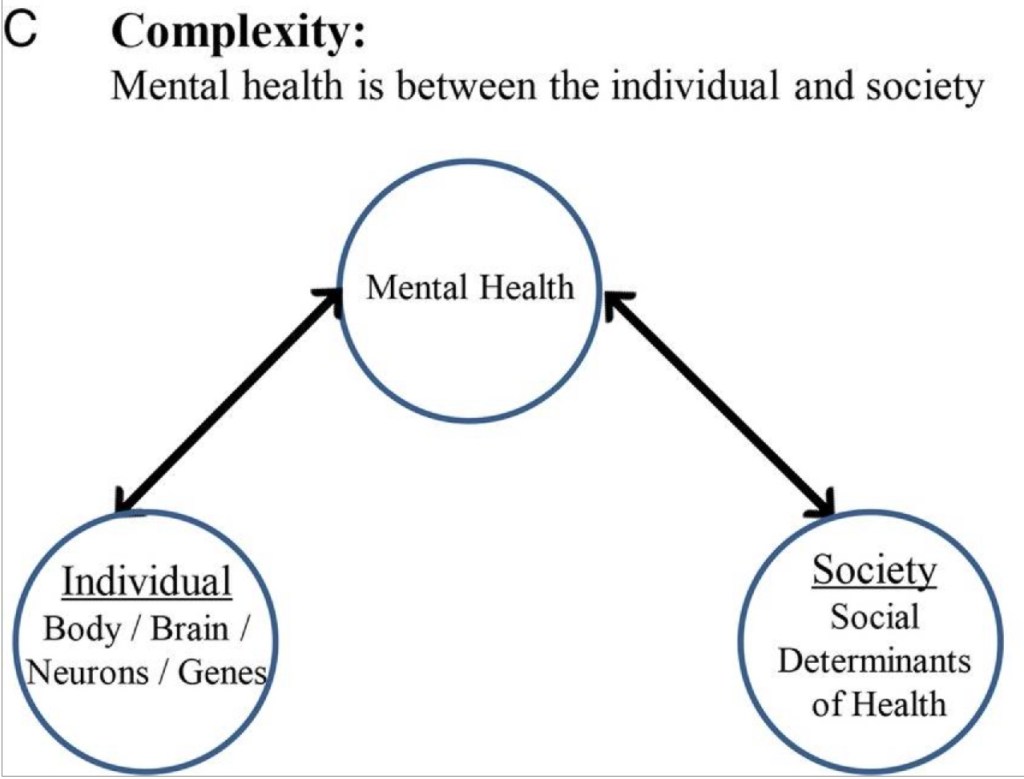

To continue from my last post about “what is mental health?” and “what am I doing?”, let’s look at another figure from the paper What is mental health? Evidence towards a new definition from a mixed methods multidisciplinary international survey:

This model argues that an individual’s mental health isn’t the sole product of that single person (because, yes, things are complex). “Society” also contributes to and affects a person’s mental health.1

The Covid pandemic provided plenty of empirical evidence that “society” has enormous influence on the mental health of individuals. Over a third of young people reported “poor mental health” and nearly half reported they “persistently felt sad or hopeless” in 2021. There were nearly 30,000 (!) more deaths related to alcohol when comparing 2019 to 2021. Two out of every five adults reported “high levels of psychological distress” at some point during the pandemic.2

The pandemic isn’t the only example of the power of “society” on mental health. Survivors of mass shootings can develop psychiatric symptoms or disorders. Residents of Flint, Michigan, could only access drinking water contaminated with bacteria, disinfectants, and lead. This contributed to elevated rates of psychological conditions like depression and PTSD. Poverty increases the likelihood of depression and anxiety.

“Imagine how many people I wouldn’t need to see if people never experienced homelessness!” I mutter (or exclaim) at least once a month. It’s not just homelessness: It’s working three jobs to make rent; it’s trying to keep the family fed and housed when one parent has major medical problems; it’s trying to leave an abusive partner; it’s trying to keep things together when a family member has an alcohol or gambling problem. Because much of my career has been in the “deep end” of the system, I often witness how misaligned and rigid institutions often bruise and scar the psyches of individuals and populations of people.

Maybe context matters more in psychiatry than in other fields of medicine. When I think, “What am I doing?”, I often wonder if I should work “upstream” in prevention and early intervention to help change these contexts. This includes advocacy for action that is outside the purview of medicine, such as lowering barriers to housing or increasing regulation of firearms.

Some physicians (and others) have argued that doctors should “stay in our lane”, that we should focus on treating conditions that we are trained to treat. Medical school didn’t teach me how to prevent psychotic disorders; it trained me to identify and treat schizophrenia. In residency I didn’t learn how to develop policy and programming to prevent war and rape; I was trained to provide care and support to someone with PTSD. I can help someone choose to put their gun away so they don’t shoot themselves; I don’t know how to organize people to persuade elected officials to change gun regulations.3

Of course, there’s a middle ground. My clinical experience and expertise give me the anecdotes and data to advocate for system changes. These system changes can improve the health of individual people. Furthermore, there are real people who have real psychiatric problems who need real help right now. As Paul Farmer said,

To give priority to prevention is to sentence them to death—almost to urge them to get out of the way so that the serious business of prevention can start.

I once worked for a medical director who often said, “I’d love to work myself out of a job.” It sounds disingenuous, but it’s true: I completely agree. How wonderful would it be if fewer people experienced psychological distress and problems with living! (Given the ongoing shortage of psychiatrists and other mental health professionals, this would be a win for literally everybody.) What if people didn’t believe that suicide was the best option? Or if people didn’t have to grapple with unending worry about where they will sleep tonight or when their next meal would be? I wholeheartedly concede that crafting legislative language and designing policies and programs are not my strengths. However, it also makes little sense to me to keep my head down and simply treat illnesses and suffering that can be prevented. Things don’t have to be this way.

(1) Again, if we’re going to be picky about words, I prefer the word “context” over “society”. “Society” suggests something uniform, when there exist microcultures within one society. For example, I’ve worked as a homeless outreach psychiatrist in New York City and Seattle. In New York I wore bright blouses with large ascots. In Seattle I wear dark hoodies. Same job, same society, different contexts.

(2) We can argue about whether these reports of distress and their associated behaviors reflect “mental illness” versus “mental unwellness”, in reference to part one of this series.

(3) While media reporting often focuses on guns and homicide, firearms cause more suicides than homicides.