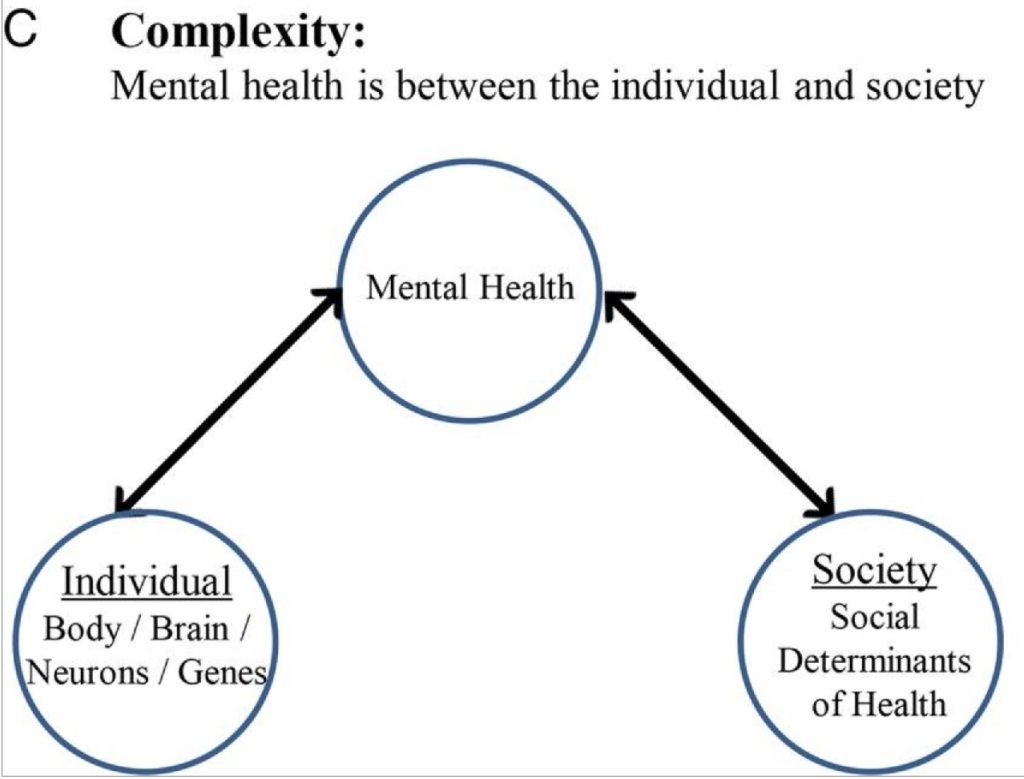

Let’s take a look at the last figure from the paper What is mental health? Evidence towards a new definition from a mixed methods multidisciplinary international survey. The authors call this the Transdomain Model of Health:

I like this model. (Do note, though, that the map is not the territory.) It reminds us of the interdependencies between and within ourselves. If our community isn’t doing well, that will affect our individual mental health. To intentionally use a trivial example (because there are WAY too many heavy things happening these days), consider a city’s baseball team. A not-so-fictional team called the Tridents has had some embarrassing games; hits are uncommon, fielding errors abound, and pitchers are giving up a lot of runs. Grumpy viewers write corrosive comments about the Tridents in the city’s newspaper. Suckers like me read the comments and feel a disjointed sense of “us”. Maybe some of these grumpy viewers are in foul moods for other reasons and they direct their ire at the Tridents because that’s easier to talk about than their alcohol or gambling problems. They would go to Cell Phone Carrier Stadium to grumble at the Tridents directly, but they are dealing with illnesses that limit their abilities to navigate social spaces. Most of us don’t feel psychologically fine when we are physically unwell.

Contrast this Transdomain Model of Health with this recent Psychiatric News article, Lifestyle Psychiatry Emphasizes Behaviors Supporting Mental Health.

The authors define “lifestyle psychiatry” as seeking

to cultivate well-being and support individuals in preventing and managing psychiatric disorders and optimizing their brain health.

(Editorial comment: I feel some vexation about “lifestyle psychiatry” because I don’t think “lifestyle psychiatry” should be a specialty with its own textbook. Every psychiatrist should practice “lifestyle psychiatry”.) While the authors concede that “patients may have cost or access barriers to traditional care” and conclude the article with a proclamation that lifestyle psychiatry is “a vital component in improving the health and well-being of people around the world”, the final sentence gives away the underlying sentiment of bootstrapping: supporting “individuals in taking ownership of their mental health and well-being” (emphasis mine).

The “social health” component from the Transdomain Model of Health is missing from “lifestyle psychiatry”, even though addressing social health will make it much easier for people to succeed in the “lifestyle psychiatry domains”:

It’s much easier to get physical exercise when there are generous green spaces, plenty of intact sidewalks, and public safety isn’t a concern. Healthy diets and nutrition are easier to achieve when fresh food is available and affordable. It’s easier to be mindful and take yoga classes when you don’t have to work two jobs to make rent. People sleep better when there’s no noise pollution; what if the affordable housing wasn’t only close to airports, trains, and freeways? Neighborhoods with “third spaces” make social relationships more likely to bloom.

To be fair, the lifestyle psychiatry authors do write of “consultation and leadership to governments, corporations, and health care systems” and informing “public education programs and community planners to support the creation of healthy communities [and] employers in creating healthy workplaces”. Their definitions, though, ultimately focus on individuals and do-it-yourself interventions with some consultation with your local lifestyle psychiatrist. (And, to be clear, I’m not saying that systems are the only issue. People do still need to make their own choices, but we can shift systems so it’s not as hard for people to make healthier choices. Life is already hard enough.)

Seattle was not anywhere near the path of totality for the total solar eclipse today. Over lunch I watched part of NASA’s live broadcast. And what a mush ball I am: I cried into my meal as I watched the skies turn to black, heard the crowds cheer and gasp, and saw the dancing corona of the Sun.

I’m not so naive to believe that being in community solves everything. However, I do believe that being in community–contributing to social health–can powerfully change the way we view and feel about ourselves, others, and the world around us. Millions of people witnessed a total solar eclipse in person or in two-dimensions today. I’m pretty sure I wasn’t the only one who cried while watching the broadcast. Three things had to be in place for this celestial event to occur: The Sun, the Moon, and the Earth. To witness this stellar occasion, we all had to be on the same planet. Maybe this is naive: I’d like to think that the shared experience of a total solar eclipse boosted our planetary social health. And, as a result, we individually experienced higher mental health today.