Tomorrow (April 22) the United States Supreme Court will hear oral arguments in the case City of Grants Pass, Oregon, v. Gloria Johnson. This article, 5 things to know about the Grants Pass homelessness case before the US Supreme Court, summarizes the issue well: “The repercussions could have national implications for how cities can regulate homelessness.” In short, if the Supreme Court sides with the City of Grants Pass, it could essentially be a crime to be homeless. (Note: “Homelessness” here refers strictly to street homelessness. The federal definition includes other populations that are not as visible, such as people living in shelters, people about to be evicted, etc.)

This brings to mind other information:

California Statewide Study of People Experiencing Homelessness. This came out in June of 2023. It’s one of the few recent surveys that examines mental health conditions and substance use among people experiencing homelessness. Over 3,000 people in various parts of California answered surveys and over 300 people participated in detailed interviews. They didn’t administer technical interviews to determine whether people met diagnostic criteria for psychiatric conditions. They instead asked people if they had ever experienced certain symptoms (e.g., hallucinations, anxiety, depression) or engaged in certain behaviors (e.g., used any substance three or more times a week) in the past or at the time of the interview. More than half of the people who responded said that they either had a mental health condition in the past or were experiencing one now. More than half reported that they had used substances in the past; about one-third reported that they were currently using any substance at least three times a week. (Note that “substance” here does not include alcohol or tobacco.)

JAMA Psychiatry: Prevalence of Mental Health Disorders Among Individuals Experiencing Homelessness. I have yet to read this paper. It’s a review and analysis of past research related to this topic (a research study of past research studies, if you will). It looks like they looked at specific diagnoses, with a call out of 44% of people experiencing homelessness experiencing any substance use disorder. Other highlights included in the abstract include prevalence rates for antisocial personality disorder (26%) (one of my most popular posts—from 2013!—is about this condition, for whatever reason… and I’ve been wondering about this one again), major depression (19%), schizophrenia (7%), and bipolar disorder (8%).

Open drug scenes: responses of five European cities. This paper is from 2014, though it holds lessons that we in the US can and should learn from. The information within disappoints everyone, which means it is probably a reasonable map to use.

Open drug scenes are gatherings of drug users who publicly consume and deal drugs.

To be clear, as evidenced by data shared above and from anecdotes from those of us who do this work, not everyone who is homeless uses drugs. Not everyone who uses drugs is homeless, either. Much of the current discourse about homelessness is related to drug use, though, which is why I bring up this paper.

The five cities described in the paper vary in size (Zurich, Switzerland, at around 415,000 people to Lisbon, Portugal, at 2.7 million people), though they each use similar strategies to reduce and eliminate open drug scenes:

- drug dependence is a health problem

- drug use behavior is a public nuisance problem

- need for low threshold health services, outreach social work, and effective policing

- appropriate combinations of harm reduction and restrictive measures

Law enforcement is needed to address the public nuisance problem. Robust health and social services that include harm reduction are needed to address the health problem. (At least two of the cities legalized heroin so people can use drugs safely in monitored settings, with hopes that they will one day use less and perhaps stop. Recall that this paper came out before the destructive wave of fentanyl overcame us.) Most cities have yet to find the “appropriate combinations” to reduce open drug scenes. (Just to reiterate, these strategies did not eliminate homelessness, only open drug scenes.)

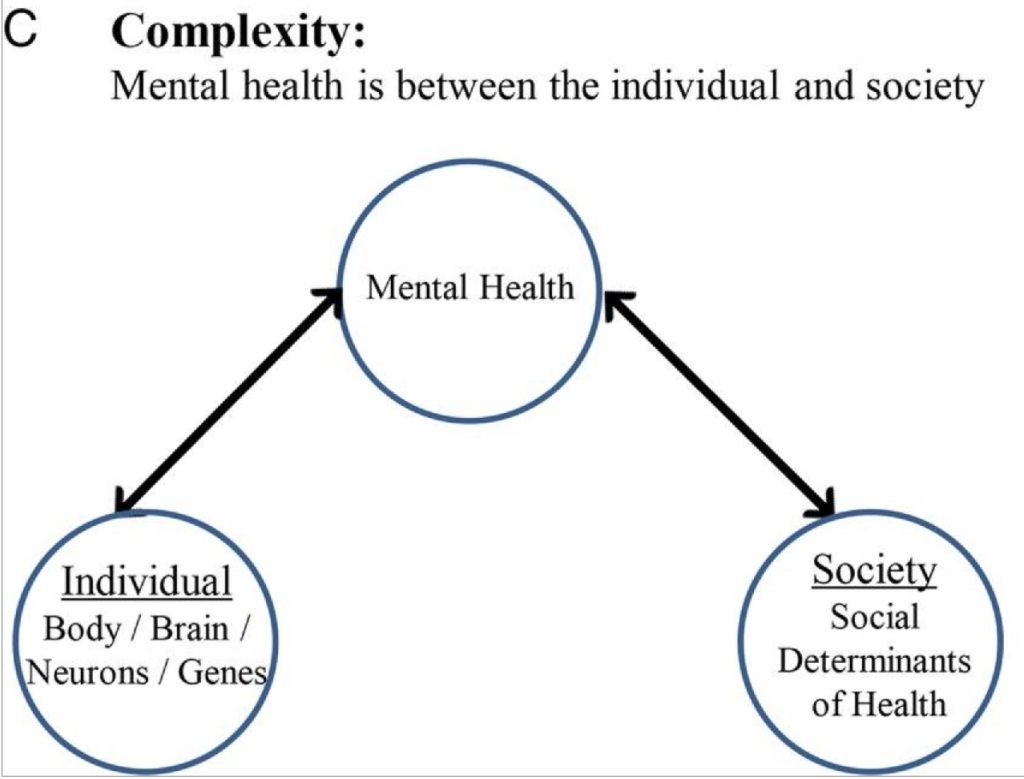

Textbook Talk: Dr. Van Yu on Housing First and the Role of Psychiatry in Supported Housing. One significant way to eliminate homelessness is to ensure that people have places to live. Lemme tell ya: It is hard to effectively treat someone’s mental health or substance use disorder if they don’t have a stable place to live. If the person can’t or won’t come to you, that means you have to go to them. If you can’t find them (because they don’t have a place to live so they move around a lot), it’s hard to make a connection to help them. Even if they want to participate in treatment, it’s challenging to Do All the Things when you don’t know where you are going to sleep. Can you imagine what you’d do or how you’d feel if you didn’t know where you were going to sleep tonight? Seeing a health care professional likely won’t be your priority. Working in a Housing First or other public setting also changes the way you think about health care: Your interventions don’t just affect one person; they affect a whole community. Conversely, the community influences your interventions as a health care professional. We naturally become systems thinkers. (Full disclosure: Dr. Yu was once my boss. I learned and continue to learn a lot from him.)

I will follow the City of Grants Pass, Oregon, v. Gloria Johnson case with interest. The problem of homelessness is complex because people experiencing homelessness each have distinct challenges. They are not a monolith. I believe that there are government officials who are sympathetic to their circumstances. I still wonder, though, what problem are they trying to solve? Is it that they don’t want people to live outside? Or that they don’t want to see people living outside?