The second instance of the word “mental” in Project 2025 is on page 6, just a few paragraphs after its first appearance in the foreword:

This resolve [“Every threat to family stability must be confronted”] should color each of our policies. Consider our approach to Big Tech. The worst of these companies prey on children, like drug dealers, to get them addicted to their mobile apps. Many Silicon Valley executives famously don’t let their own kids have smart phones. They nevertheless make billions of dollars addicting other people’s children to theirs. TikTok, Instagram, Facebook, Twitter, and other social media platforms are specifically designed to create the digital dependencies that fuel mental illness and anxiety, to fray children’s bonds with their parents and siblings. Federal policy cannot allow this industrial-scale child abuse to continue.

This 100-word paragraph features inflammatory language sure to capture a caring parent’s eye: drug dealers! addicting! child abuse! Let’s take a closer look:

Are social media companies preying on children like drug dealers? I don’t know the intentions of leadership at social media companies, but there is evidence that these companies make mega amounts of money from the attention of youth. One paper revealed that, in 2022, “advertising revenue from youth users ages 0–17 years [was] nearly $11 billion”.

Billion with a B! Let’s name names. According to the same paper:

The greatest advertising revenue profits derived children [sic] ages 0–12 years old was from YouTube ($959.1 million), followed by Instagram ($801.1 million) and Facebook ($137.2 million). Among youth ages 13–17 years old, the greatest estimated advertising revenue was generated on Instagram ($4 billion), TikTok ($2 billion), and YouTube ($1.2 billion).

(It’s true: Only old people use Facebook.)

How do these numbers compare to other businesses?

| Entity | Revenue (one year) |

| Los Angeles Dodgers | $549 million |

| Taylor Swift | $1.04 billion |

| Cannabis tax revenue | $3 billion |

Instagram made more money than Taylor Swift!

Is it true that “many Silicon Valley executives famously don’t let their own kids have smart phones”? It looks like the answer is yes, or at least they restrict their kids’ access to media.

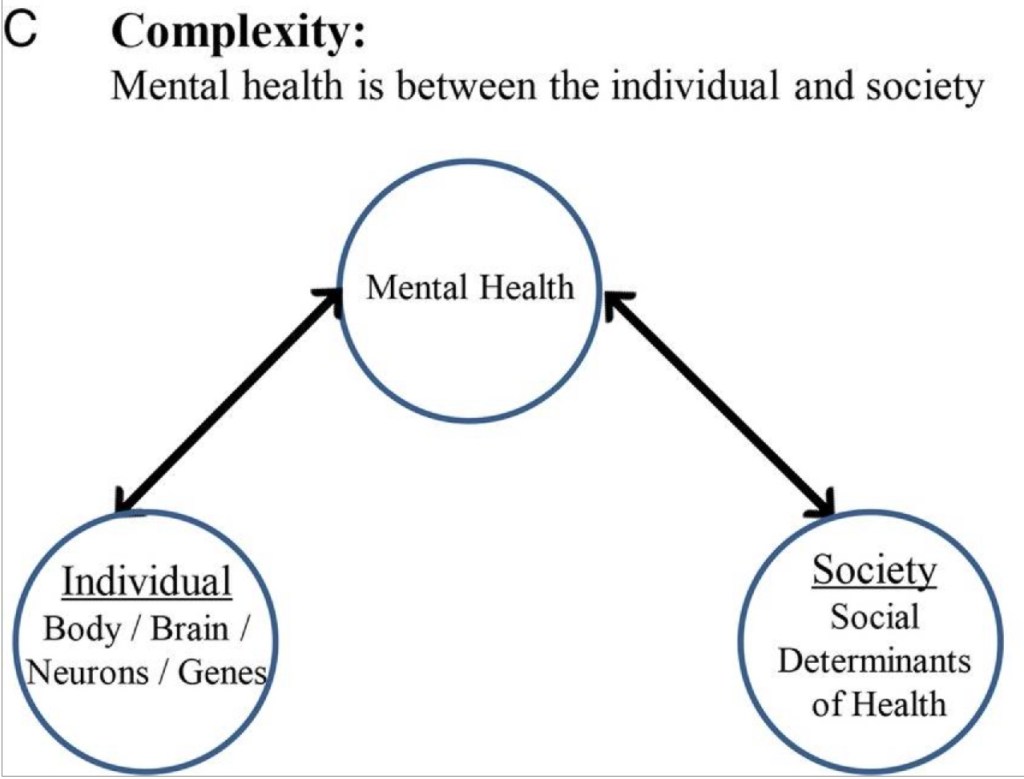

Do social media platforms “create the digital dependencies that fuel mental illness and anxiety”? In short, the answer is yes, but not for every child and adolescent.

The excellent Surgeon General Vivek Murthy issued an advisory about the effects of social media on youth mental health:

Usage of social media can become harmful depending on the amount of time children spend on the platforms, the type of content they consume or are otherwise exposed to, and the degree to which it disrupts activities that are essential for health like sleep and physical activity. Importantly, different children are affected by social media in different ways, including based on cultural, historical, and socio-economic factors.

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) has a Center of Excellence on Social Media and Youth Mental Health that includes a policy statement on the risks and benefits of social media use and how media can affect the development of young minds.

The American Psychological Association has shared information about relationships between the amount of time youth spend on social media and mental health outcomes (more time spent associated with worse outcomes), why young brains are especially vulnerable to social media, and called out social media companies to improve the safety of their products.

Does social media fray children’s bonds with their parents and siblings? The framing of their argument suggests that the fraying of bonds is entirely the fault of children using social media. Kids don’t have the money to buy phones and computers themselves. Humans learn through observing.

AAP correctly states:

Parents’ background television use distracts from parent–child interactions and child play. Heavy parent use of mobile devices is associated with fewer verbal and nonverbal interactions between parents and children and may be associated with more parent-child conflict. Because parent media use is a strong predictor of child media habits, reducing parental media use and enhancing parent–child interactions may be an important area of behavior change.

This research paper about problematic media use in early childhood points out that “parent’s PMU [problematic media use] remained the strongest correlate of concurrent child PMU” and “parental warmth and responsiveness might be protective of the development of PMU among young children”.

In sum, the authors of Project 2025 have some legitimate and evidence-based concerns about the adverse effects of social media on kids.

So why do the authors of Project 2025, who have voiced support of the incoming President, seem to have no issue with his own social media platform (Truth Social)?

And why, after vilifying Silicon Valley executives, is there no outcry about Elon Musk, now an owner of a (financially failing) social media company, having a position in the federal government? (Also, is it efficient to have two leaders of the Department of Government Efficiency?)

And if the authors of Project 2025 want to change federal policy to prevent “industrial-scale child abuse”, then surely they want to prevent deaths of children. For [the] third straight year, firearms killed more children and teens, ages 1 to 17, than any other cause including car crashes and cancer. There are solutions to prevent guns from killing kids. Strange that there are absolutely no firearm policies in Project 2025!