On medicine being agents of social control. These three news articles highlight the misuse of authority within the context of medicine:

Delta ‘weaponized’ mental health rules against a pilot. She fought back. In short, a woman named Karlene Petitt was (and remains) a pilot for Delta airlines. In response to a general exhortation from Delta leadership to speak up about safety issues, she submitted reports that did just that. In return, Delta leadership sought to silence her and initiated a process to deem her “too mentally unstable” to be a pilot. Delta recruited a psychiatrist who provided a diagnosis to support this argument. (The psychiatrist apparently diagnosed her with bipolar disorder because of her many accomplishments—“well beyond what any woman [he’s] ever met could do”.) She contested this and took legal action. She won.

How a Chinese Doctor Who Warned of Covid-19 Spent His Final Days. This 16-minute video investigation includes remarks from a physician who provided care to Dr. Li Wenliang, the ophthalmologist in China who tried to alert the public about Covid-19 before he died from the infection himself. Around minute 11 of the video, both the narrator and the physician comment that hospital administrators wanted the health care team to provide an intervention (ECMO) that was not clinically indicated. However, it would buy the hospital administrators time and allow the hospital to report that the health care team “did everything”. The physician states that using ECMO would have been both a violation of medical care and medical ethics. This is an example of “reputation management” superseding clinical judgment.

Woman’s legal quest illuminates the rights of hospital patients who want to leave. Here, a woman voluntarily agreed to enter a psychiatric hospital for care, but was not permitted to leave upon request. Available documentation suggests that she was not at risk of harming herself or others at the time of her request to leave. Under these circumstances, that means the hospital was essentially holding her captive. (This is reminiscent of “On Being Sane in Insane Places“, where context affects how we evaluate situations.) Even worse:

“All patients admitted to the facility,” the manager said, meet the criteria to be involuntarily committed, “even voluntarily admitted patients.”

The manager told DOH investigators that staff “do not orally notify voluntary patients” of their right to be released immediately, despite a state law requiring this disclosure. If they did, he said, “Everybody would be asking to leave.”

Those two short paragraphs reflect poorly on the hospital in question.

On the death penalty. The first two articles present opposing perspectives on the death penalty. The third article provides a first-person account of being in prison, which adds context to the first two articles.

If Not the Parkland Shooter, Who Is the Death Penalty For? Here, the author describes justifications for punishment:

Society embraces four major justifications for punishment: deterrence, rehabilitation, incapacitation and retribution.

I’ve not seen it described this way and appreciate the framework. This might be a red herring: The author also argues that the Parkland shooter’s “human dignity requires his just punishment [with the death penalty] as an end in itself”. I struggled to wrap my head around this one: We usually cite people’s humanity and dignity as reasons to keep them alive, not to kill them.

I Wish the Jury Had Not Sentenced My Family’s Killer to Death. In contrast, the author here argues how the death penalty, while maybe just, doesn’t actually solve any problems. It instead only prolongs suffering for the families of victims. Also, “death by incarceration” is still death. (I also appreciated her firm recommendations about how to support people who experience unspeakable tragedies.) While the author of the previous pro-death penalty piece focuses more on theory and logic, the author here focuses more on practicalities and emotions. Both models have value. Both articles made me consider my own stance on the death penalty.

Prisoners Like Me Are Being Held Hostage to Price Hikes. The author of this piece is currently in prison. Though I have never worked in prison, I have worked in jail. His descriptions about commissaries, food items, and access to various items seem similar to what I have observed in jail settings. (It also continues to baffle me how businesses are allowed to make money off of people in jail—including medical care!!!) Nobody is spared from inflation and price hikes.

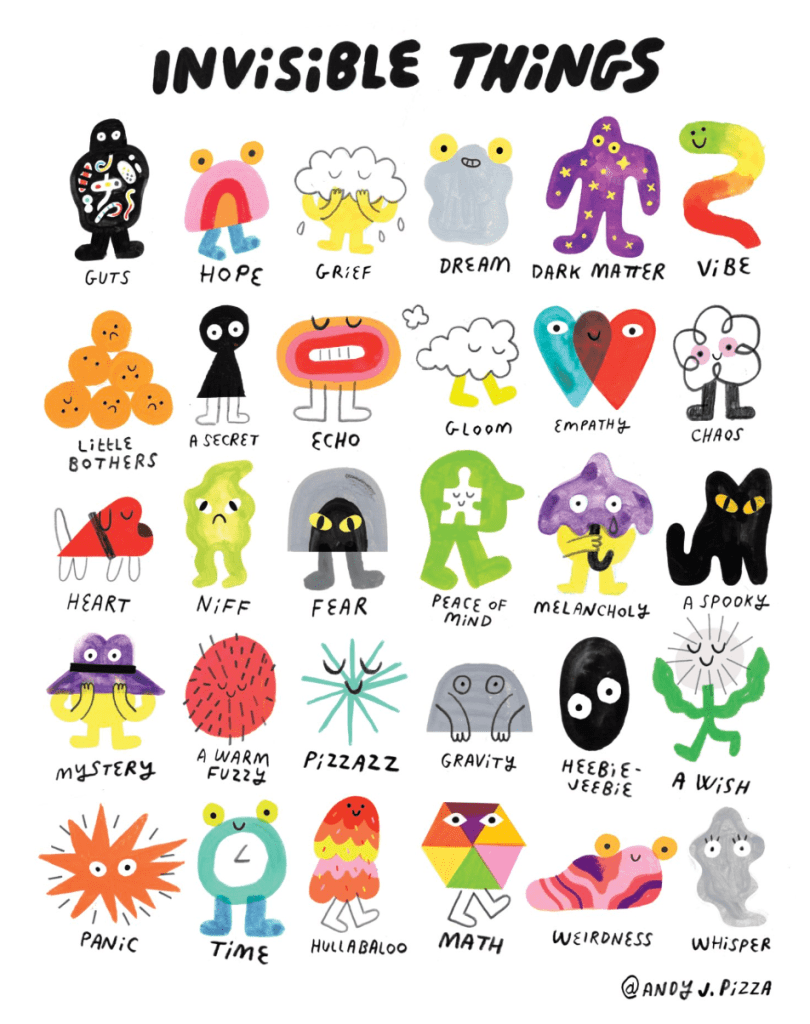

To end this on a lighter note: This artwork from Andy J. Pizza made me feel a variety of invisible things: